The application that engages elementary school students by gamifying creative reading and writing

By Steven Chase

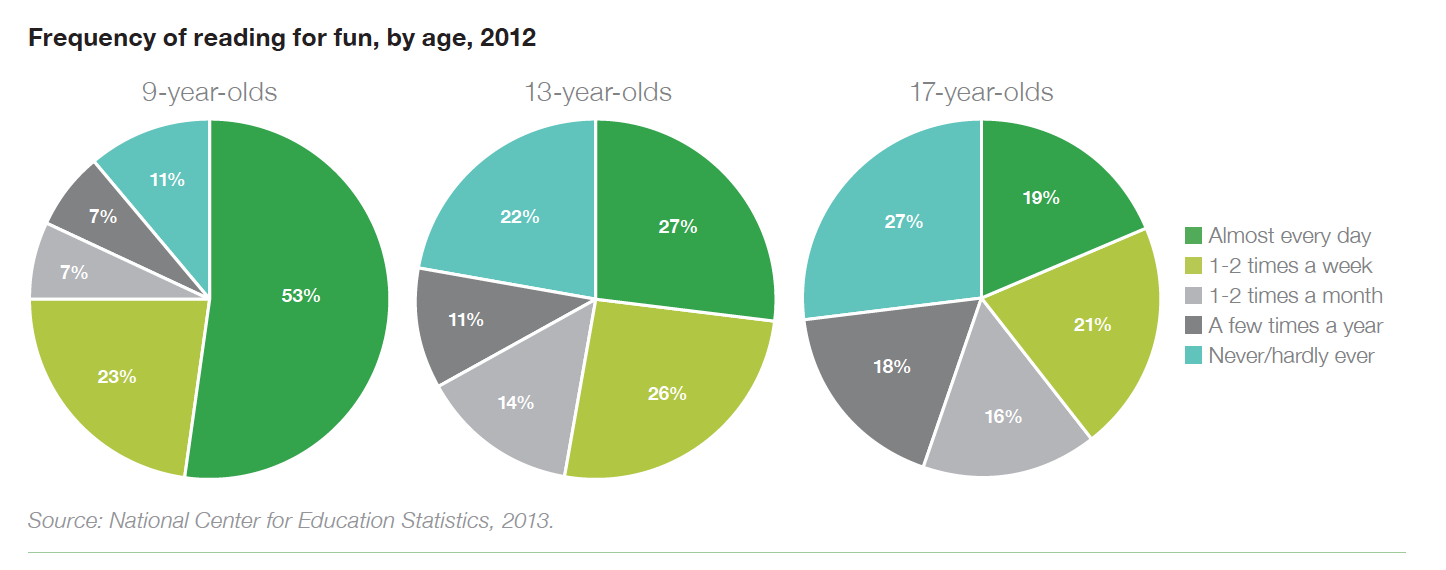

Across the nation, the frequency with which students are reading and writing is decreasing. The drop is especially sharp for elementary and high school students. A study done by Common Sense Media (1) discovered that the number of elementary school students who “never” or “hardly ever” read has roughly tripled in the last 30 years, from 8% to 22%. Additionally, the proportion of daily readers drops from 48% at the age of 8 down to 24% at the age of 15. A full third (33%) of 13-year-olds admit to reading no more than once or twice a year!

The amount of daily readers drops from 53% to 19% from ages 9 to 17 while those who ‘never/hardly ever’ read increases from 11% to 27%. (1)

The amount of daily readers drops from 53% to 19% from ages 9 to 17 while those who ‘never/hardly ever’ read increases from 11% to 27%. (1)

These are troubling statistics we are seeing coming from young students. Especially when you consider how important this stage of their development is. Reading and writing during the elementary years is crucial for the development of lifetime creative abilities. However, instead of picking up a book, children are turning to their screens. Fortnite is replacing ‘Harry Potter’. Mario Kart is replacing ‘Holes’. With improved technology came 24/7 access to screens and the advent of the concept of ‘screen time’. Parenting books have vilified screen-time, obsessed with limiting the amount of time that children are exposed to screens. But what if the issue isn’t with the amount of screen time, but with the material that is being consumed through the screens? Screens have pervaded children’s lives and they are drawn to them. Instead of trying to force technology out of their children’s lives, parents should be focused on harnessing their power for good.

Enter Story Squad. Story Squad is the brainchild of Graig Peterson and Darwin Johnson. Graig has been an educator for over a decade and understands how important creative reading and writing is to the development of a young student. He has seen the downward trend of students reading and writing less across his career and wants to re-engage elementary-aged students. His vision is to bring the same game structure that the kids enjoy so much, the reason they spend hours on Fortnite, to reading and writing. His Story Squad application will gamify creative writing. Students will be able to select a book to ‘play’. The children are given a short excerpt from the book to read and will then be able to choose from a selection of writing prompts. These prompts encourage students to bring a character from the story off on their own side quest; to use their imagination to create their own unique plots and adventures, even drawing illustrations as they go. Upon completion, these writings and illustrations will be uploaded to the Story Squad application where they will face off against other players. Winners will be chosen by popular vote weekly and students will collect badges and achievements as they go, similar to traditional games. Driven by friendly competition and a sense of accomplishment, students will be eagerly picking up Story Squad. By working to rise up the leaderboards, the students will be improving their creative writing skills while having fun.

Children will be able to pick a mission and then will read, write and draw, submitting their work to compete against others.

Release 1: Transcription and Complexity Evaluation

I am a data scientist working as part of a nine-person cross-functional team whose goal is to turn Graig and Darwin’s vision into reality. While our five web developers worked on creating a kickass front end graphical user interface for the student and parent to interact with, our three-member data science team got to work on creating some behind the scene magic that makes the application run.

To prepare the Story Squad application for its first release, our data science team was tasked with receiving an uploaded written story, transcribing it, and then evaluating the complexity of the student’s writing. This complexity metric would be used for two things. Initially, a history of the student’s complexity metrics would be displayed to the parental account. Hopefully showing how the student’s writing has improved as they continue to use Story Squad. As part of the second release, it will be used to group competitors together based on similar writing levels.

While in theory, this seemed straightforward; anyone who has tried to read a young child’s handwriting knows how difficult it can be for a human to understand their writing, let alone a computer. Ideally, we would have been able to build and train our own Optical Character Recognition (OCR) model so we could customize it to our specific needs. For us, that would have meant training an OCR model on specifically children’s unkempt handwriting. Unfortunately, we did not have access to the amount of children’s handwriting data that would have allowed us to create a robust model. Instead, we turned to the second-best option. Google Cloud Vision provides an industry-leading OCR that is specifically trained on handwriting, known as a Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR) model. While this is trained on adult handwriting as opposed to children’s handwriting, it still performed better than any other model we tested.

After transcribing the student’s handwriting, all we had left to do for release 1 was to assign the complexity score. Again this task, on the surface, seemed simple enough. The Python package textstat was built specifically to “calculate statistics from text to determine readability, complexity and grade level of a particular corpus.” Perfect! This package includes a dozen different formulas that we could leverage to provide complexity metrics for our student’s writings. However, as we looked into implementing textstat, we discovered some shortcomings both with the textstat package itself, and the text we would input into the functions. First, textstat is built and designed around professionally written and edited documents. It would not be fair to attempt to evaluate the writing of an eight-year-old against such standards. Second, the quality of the input text was not on par with what textstat was trained on. While the Google Cloud Vision HTR had done its best with the children’s handwritten submissions, it was still too rough to try to evaluate sentence structure, syllables or more complicated natural language processing methods. We also discovered that the quality of the transcription was entirely reflective of the handwriting of the child. Sloppy handwriting led to missed punctuation, words being transcribed out of order, and a perceived increase in spelling mistakes.

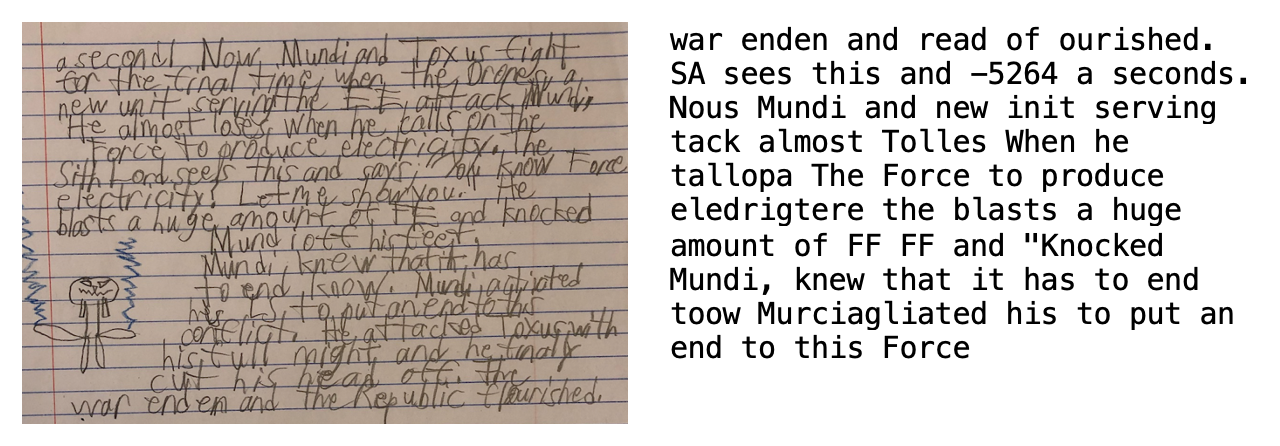

Poor handwriting led to poor transcriptions which affected the complexity metrics the textstat package used.

Poor handwriting led to poor transcriptions which affected the complexity metrics the textstat package used.

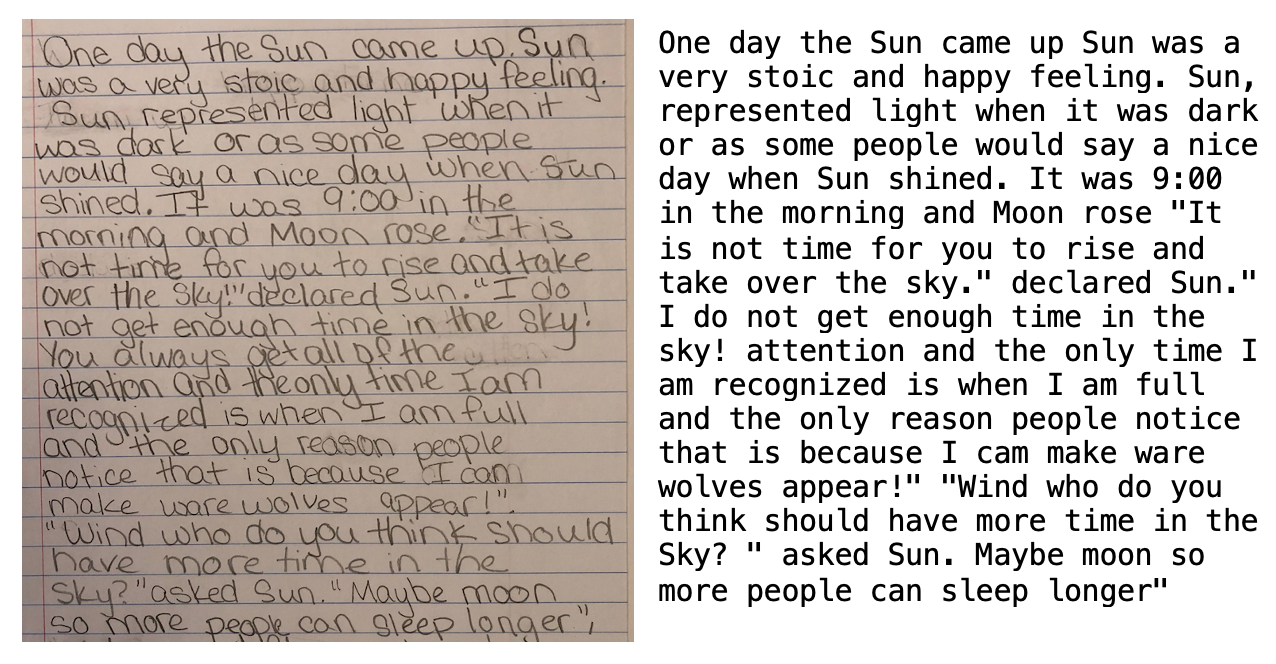

Better handwriting led to far less transcription errors and better complexity metrics.

Better handwriting led to far less transcription errors and better complexity metrics.

Upon reflecting on this dilemma, we decided to create our own complexity metric formula based on features we knew we could reliably extract from the text regardless of the quality of the transcription. After all, our goal was to evaluate the content of the children’s writing itself, not the quality of the student’s handwriting. That was the genesis of the Squad Score formula!

After conversations between our data science team members, numerous rounds of data exploration, as well as conversions with our stakeholders, we narrowed our metrics down to the five features we believed were least susceptible to transcription errors: story length, average word length, percentage of quotes, and the percent of unique words.

Unfortunately, as we currently have a lack of labeled data, we are not able to fine-tune the weights to provide a more accurate model. Upon asking our stakeholders, we received a ranking of twenty-five of the stories from our dataset. This limited amount of labeled data has been enough to confirm that we are on the correct path but is too small and subjective to provide any actionable insights. Our current working formula simply adds a weight of one to each of these metrics and adds them together to produce our Squad Score.

While there is a lot of room for improvement in our current complexity evaluation model, it has been a good baseline to work off of and satisfied the requirements of our minimum viable product (MVP) for release 1.

Baseline Complexity Metric Model

# Instantiate weights

weights = {

"story_length": 1,

"avg_word_len": 1,

"quotes_number": 1,

"unique_words": 1

}

# Scale metrics with pickled MinMax Scaler

scaler = joblib.load('MinMaxScaler.pkl')

scaled = scaler.transform([row[1:]])[0]

# Generate scaler to create desired output range (~1-100)

range_scaler = 30

# Weight values

sl = weights["story_length"] * scaled[0] * range_scaler

awl = weights["avg_word_len"] * scaled[1] * range_scaler

qn = weights["quotes_number"] * scaled[2] * range_scaler

uw = weights["unique_words"] * scaled[3] * range_scaler

# Add all values

squad_score = sl + awl + qn + uw

Release 2: Gamification!

The objective of our second release is to introduce the gameplay framework that will drive the competition between the participants. Currently (as of 10/23/2020) we have implemented half of the gamification release. For this portion the students are placed into groups of four and paired with a teammate to face off 2v2. The goal of our data science team was to create these clusters of four by grouping students with the most similar level of writing. After completing the features for release 1, we had the ability to successfully receive, transcribe and assign complexity metrics to each user’s uploaded content. To reach our MVP for clustering, we simply used the ranked complexity scores to build the groups of four. In the future, we will be building a data science database to store the individual metrics of each submission allowing us to implement a NearestNeighbor model we have already built to provide clusters based on similarity between specific metrics instead of simply the overall complexity metric.

The largest challenge that we had with grouping users was considering what to do with what we called ‘the remainder problem’. Very rarely would the number of users be evenly divisible by four. Naturally the final grouping could have only one, two or three members assigned to it. As the gameplay required that each group had exactly four players, we had to come up with a solution to this problem. Our solution was to create ‘bot’ players. We would fill out the group by pulling in a similar writing piece that had been submitted by a user from a different group. Then a ‘bot’ would be implemented to auto-vote and complete the rest of the gameplay for that submission. Additionally, we wanted to limit the number of ‘bot’ players to one per group. In other words, if there was a single player left to be grouped, we did not want to build a group with one user and three bots. Instead we spread out the bots, creating three groups of three student users with one lone bot player.

Side note: Moderation

Something that was not specifically required from the stakeholders, but an issue that we were concerned about as a data science team, was moderation. Users of the Story Squad application will be uploading drawings and written stories which will then be shown back to other students in their cohort. As the target demographic for the application is 8-12-year-old children, we wanted to make sure that they were not being exposed to any inappropriate material. We sought to create an automated moderation system that would screen both the user’s drawings as well as the language used in their written stories. If inappropriate content was detected, we would raise a flag to an administrator who would confirm the inappropriate material.

To moderate the images, as we were already connecting to Google Cloud Vision API, we leveraged their SafeSearch method to flag any material that returned a 3 (possible) or higher in containing ‘adult’, ‘racy’ or ‘violent’ material. To moderate the written stories, after transcribing the text we compared each word to a dictionary of bad words and phrases. If there are any matches, a flag will be raised to the administrator’s board.

In order to be in compliance with the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Rule (COPPA), our stakeholder currently has administrators to review every submission. The automated process that we created will help these administrators prioritize their work and prove invaluable as the application scales.

Looking to the Future:

As we continue to work towards a more complete application, we look forward to both implementing new features and improving on the MVP features we have already shipped. As mentioned earlier, a limiting factor to the data science work that we have done so far is the lack of samples of children’s handwriting to train an OCR and a lack of labeled data to improve the accuracy of our complexity model. As a solution to both of these, our stakeholders have opened a free daily writing contest. Besides offering a creative outlet available to any child who wants to participate, this will also serve to source both handwriting samples and labeled training data. The goal is to source enough data to begin training our own OCR by the end of 2020.

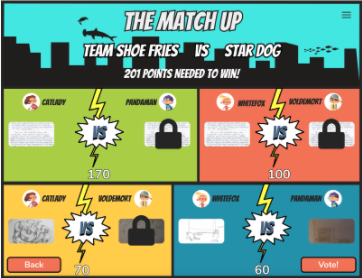

As we eagerly await a larger dataset to work with, we continue working on the second half of the framework for the gameplay. After being grouped together, students will have their stories face off against each other. Each student will have 100 points to divide as they see fit between their story and their teammates’. Then they will face against another pairing and the written stories will go head to head. Voting on the matchups will be done by the application users as a whole and the winning submissions will claim the amount of points that were at stake for that matchup. Winners will be tracked and rewarded. Fun will be had all around and most importantly, learning and creative growth will once again be instilled in the children’s lives!

Get your child to Story Squad Up! Here